Since the financial crisis, the euro area current account, made up mostly of the trade balances of the individual countries, has moved from rough balance into a clear surplus. But the underlying rebalancing across economies within the euro area has been highly asymmetric, with some debtors, like Greece, Ireland, and Spain, seeing large current account improvements (sometimes into surplus), while creditors, like Germany and the Netherlands, have basically maintained their surpluses (Chart 1). A set of new staff papers look at the drivers of the improvements in debtor current accounts and the persistence of creditor current accounts, and whether these developments are a cause for concern.

A turning point in competitiveness?

Many debtor economies have seen their unit labor costs decline, improving competitiveness and boosting their current accounts. We looked in detail at recent competitiveness gains in euro area debtor economies, finding them to be largely driven by declining unit labor costs (Tressel and others, 2014 and Tressel and Wang, 2014). But Greece and Ireland’s labor cost declines have been due to a roughly equal mix of declining wages and employment, while Spain’s has been due to declining employment (Chart 2). In other words, the bulk of competitiveness improvements in debtor economies has been accompanied by declining domestic demand and rising unemployment. This raises questions about the durability of the current account improvements in these economies: when domestic demand recovers in these economies, will current account deficits re-emerge?

Too much thrift?

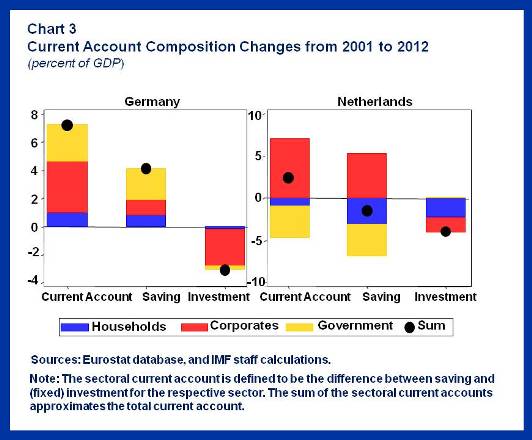

At the same time, many creditor economies have had large and persistent surpluses, driven by both higher saving and lower investment. We looked at the composition of surpluses and deficits in the euro area (Bluedorn, Wang, and Wu, 2014). Both private (corporate and household) and public saving in Germany rose over the past decade, contributing to an overall saving rise of 4 percent of GDP (Chart 3).

Meanwhile, overall investment declined by about 3 percent of GDP, from 20 percent of GDP in 2001 to about 17 percent in 2012. The Netherlands (another large surplus economy) though has seen declines in both overall saving and investment, but the investment decline has been larger (from about 21 percent of GDP in 2001 to about 17 percent in 2012). Breaking it down by sectors, it becomes clear that the Netherlands’ larger surplus is entirely due to the corporate sector. Restrained domestic demand (high saving and low investment) is part of the story behind the persistent surpluses in the creditor economies.

Towards a more “balanced” rebalancing…

Large and persistent surpluses in creditor economies contribute to a stronger euro, making it tougher for euro area debtor economies to adjust. A stronger euro exacerbates the external competitiveness gap facing debtor economies and also contributes to weak euro area inflation (see blog on “lowflation” in the euro area).

Taken together, these features suggest an “unbalanced” rebalancing—it seems to largely rely on anemic domestic demand in debtor economies and restrained domestic demand in creditor economies. They also point to a truism: appropriate adjustment is about undertaking policies to achieve both internal (reducing output gap and unemployment) and external balance (a more sustainable current account).

To make the rebalancing more robust, policies are needed to boost investment in creditor economies and structural reforms to raise productivity in all euro area economies (through further liberalization of product and service markets and reforms to make labor markets more flexible). These would raise potential growth across the board and help output gaps close faster. Breaking out of the current “lowflation” environment would also ease adjustment, by opening up space for faster relative price changes within the euro area.